Behind the scenes: wood and insect findings on Exmoor

The remains of an ancient, buried woodland have been discovered during peatland restoration works undertaken by the South West Peatland Partnership. Phil Wright, Historic Environment Officer, shares an update on exciting results on the age of the findings and insect species found within the peat, and how this might help us unearth more about the past of the peatlands in the months ahead.

Back in December 2022, a large fragment of wood was discovered within the peat at Alderman’s Barrow Allotment. The SWPP was constructing leaky log dams on this National Trust managed site, aiming to slow the flow of water through the valley, improve water quality flowing off site, keep carbon stored in peat and enhance wildlife habitat.

The wood was spotted by one of the contractors who called me over to have a look, which is standard practice when anything out of the ordinary is encountered. We carefully recovered it and sent off a sample for radiocarbon dating. It turned out to be the trunk of a willow tree dating to the early Neolithic (3940-3650 Cal BC). Further towards the base of the valley the works revealed a prehistoric woodland floor layer, composed of fragments of trunks, small branches and twigs that had accumulated during the late Neolithic and middle Bronze Age (2860–2570 Cal BC to 1400–1220 Cal BC).

Early Neolithic wood found in December 2022 (3940-3650 Cal BC)

That means we’re looking at fragments of trees growing in this spot around 3,500-6,000 years ago. This is the time that some of the earliest monuments were constructed on Exmoor, with stone rows and settings thought to have been erected from the late-Neolithic and barrows and cairns constructed in the Bronze Age. As well as Alderman’s Barrow, which lends the site its name, the earthwork remains of two prehistoric round houses are located within just a few hundred metres of the restoration works.

Despite being thousands of years old, the wood looks like it could have been buried yesterday. It’s incredible to see. Peat contains very little oxygen, which means that organic materials like wood can survive for thousands of years if the peat remains in good condition, but it’s always exciting to get a find like this.

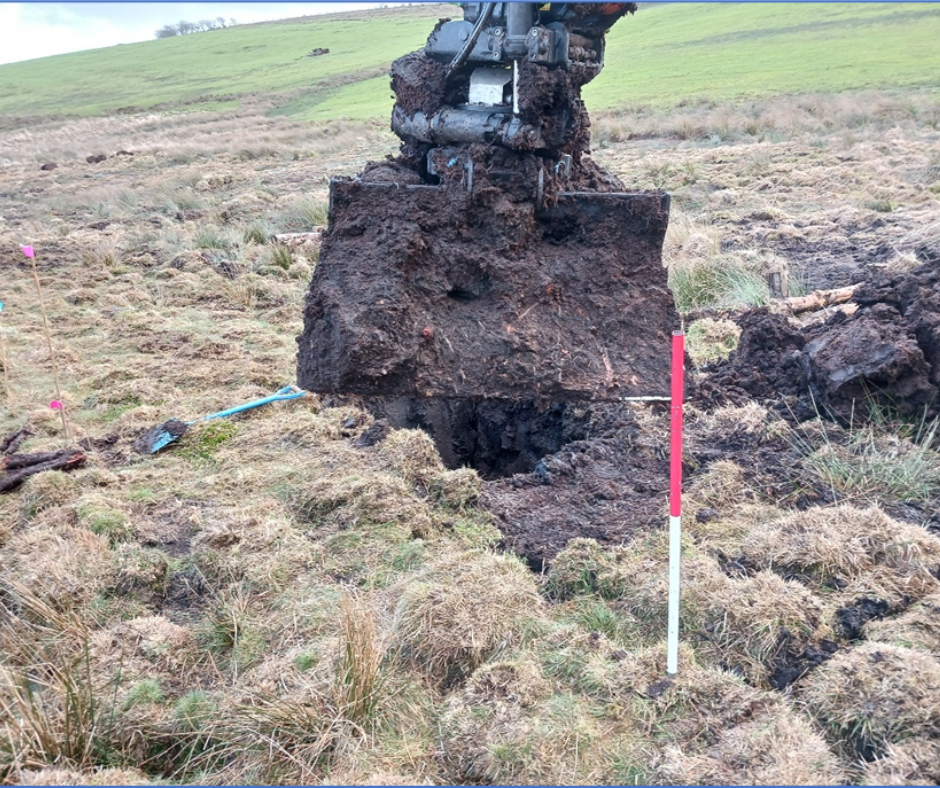

The Neolithic and Bronze Age ’forest floor’ layer, encountered at the base of a sequence of peat between 1.5m and 2m deep

We soon got the experts at Wessex Archaeology involved to take more samples of the peat and undertake further analysis of the remains. Their assessment revealed the presence of tree species including willow and alder, together with frequent seeds of rushes, sedges that are associated with damp conditions. The waterlogged peat was also suitable for the preservation of prehistoric insect remains, which is particularly exciting as insects often have very narrow environmental requirements. These included beetle species characteristic of slow-moving or stagnant water (e.g., Hydraena riparia) and waterside vegetation and trees like alder and willow (e.g., Agonum fuliginosum).

The Neolithic and Bronze Age ’forest floor’ layer, encountered at the base of a sequence of peat between 1.5m and 2m deep

By looking at all these remains together, something the specialists like to call a ‘multi-proxy’ approach, it’s possible to imagine what the prehistoric valley mire would have looked like in extraordinary detail. Scrubby woodland would have bordered a slow-moving stream in the valley bottom, with areas of standing water also present, providing the conditions for waterside vegetation as well as damp litter and moss (including sphagnum) that would have provided a habitat for insects still found in similar environments today. In short, the valley mire would have looked a little more like it appears today after the peatland restoration work.

The remains recovered from the peat last winter still have enormous potential for further research. Looking at pollen could help us to understand how the valley mire sits within a wider landscape context. Charcoal has also been found within the samples, suggesting locally occurring fires. The remains not only have the potential to help us to further reconstruct the past landscape in which surrounding prehistoric monuments were built but might also help us unpick the role of climate and human activity in the changing landscape over millennia.

The work is also a reminder of the need for Historic Environment Officers like me to be an integral part of peatland restoration from planning to works progressing, ensuring that our approach can help enhance our knowledge of the past, whilst protecting this important archive from further damage and erosion.

Close-up of the Neolithic and Bronze Age ’forest floor’ layer in a digger bucket

View more photos of the wood and insect findings at this blog here.